Rachel Farmer is a fourth-grade teacher in Brooklyn who defies the stereotype of the exhausted teacher, run down by poor inner-city schools. Instead of burned-out, Rachel is lit up — and so are her students.

Rachel Farmer is a fourth-grade teacher in Brooklyn who defies the stereotype of the exhausted teacher, run down by poor inner-city schools. Instead of burned-out, Rachel is lit up — and so are her students.

The kids read more books than any other class in the city of New York, placing them at the pinnacle of NYC’s Accelerated Reading Program. This is a story of how Rachel beat the odds using a playful (improvisational) approach to teaching…

Her class is a New York City success story. Eighty-five percent of the students were ranked on or above reading level for their age, and 92 percent were on or above level in math. Her students love to read so much (“Harry Potter” is a favorite) that she often needs to tell them to stop so they can do other activities.

How did Rachel beat the odds at PS/IS 165 in Brownsville, Brooklyn, her public school? The answer lies in her playful (improvisational) approach to classroom learning.

As the teachers got better as improvisers, they learned how to integrate the games into a math or history or geography lesson. Further, they advanced their ability to relate with students as part of a learning ensemble, that could succeed together, with nobody left behind.

Rachel practiced the improv games with her students every day. She noticed an immediate difference in classroom performance: the young people were focused, more attentive, more excited about succeeding and excited about supporting their fellow students to succeed. The games presented a challenge – for everyone.

The “Yes-And” game, for example, is designed to teach students how to “accept conversational offers.” Children create a collective story where they have to build upon what the previous speaker says — relating to each statement as an improvisational “offer.” As they go around the circle, adding new sentences onto the collective story, each child starts his/her sentence with the words “yes, and.” The game requires students to stretch to learn a new way of communicating that includes listening and focusing on what the other person is saying.

The “Yes-And” game, for example, is designed to teach students how to “accept conversational offers.” Children create a collective story where they have to build upon what the previous speaker says — relating to each statement as an improvisational “offer.” As they go around the circle, adding new sentences onto the collective story, each child starts his/her sentence with the words “yes, and.” The game requires students to stretch to learn a new way of communicating that includes listening and focusing on what the other person is saying.

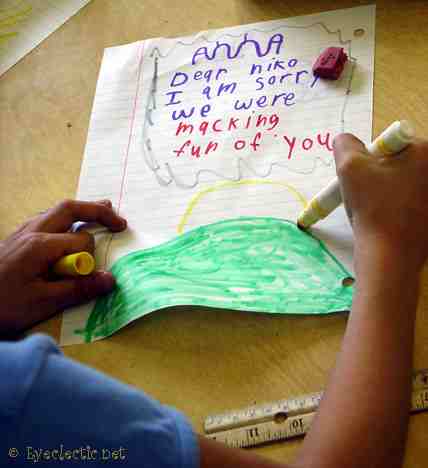

Most of Rachel’s students knew how to negate, disagree and argue, but it was much more difficult for them to accept and build upon their classmates’ contributions. Rachel and her colleagues discovered that performance games could have enormous value in creating the kind of group environment in which students can support one another.

For example, one day their assignment was to perform the “number game.” In this game, students stand in a circle and count out loud from one to ten, with only one person speaking at a time. If more than one person calls out a number, the group must start over. This game requires the students to listen, look at each other and concentrate. After practicing, each group of five or six students had to perform the game for the entire class. They were given only one chance to succeed. All the groups got it right, except one. The class asked Rachel if the unsuccessful group could have one more chance. Rachel agreed. When they succeeded, the class applauded.

For example, one day their assignment was to perform the “number game.” In this game, students stand in a circle and count out loud from one to ten, with only one person speaking at a time. If more than one person calls out a number, the group must start over. This game requires the students to listen, look at each other and concentrate. After practicing, each group of five or six students had to perform the game for the entire class. They were given only one chance to succeed. All the groups got it right, except one. The class asked Rachel if the unsuccessful group could have one more chance. Rachel agreed. When they succeeded, the class applauded.

Rachel was awarded a Developing Teachers Fellowship from the East Side Institute for the school year 2006-2007. The 10-month fellowship program, led by Lois Holzman (www.loisholzman.net), Institute director and author of Schools for Growth: Radical Alternatives to Current Educational Models, and Carrie Lobman, an assistant professor of education at Rutgers University, provides ongoing training for developing teachers’ capacities to create more collaborative, creative, playful and participatory learning environments for themselves and their students. A select group of NYC public and charter school teachers are chosen each year and given a $2,500 stipend for the year, along with the training and classroom supervision.

On The Need for a Program in Schools (from the Institute’s Website):

Many teachers feel unprepared for the complex challenges of today’s classrooms: mixed learning styles and grade levels; cultural diversity; lack of motivation – all with the pressure to raise standards. In order to meet these demands, teachers need new tools for developing a rigorous and inclusive community in the classroom.

Whether they’re working with a small group or a class of 40, whether they are teaching workshop style or “chalk and talk” teaching to the test, or engaging in creative play, teachers are always working with groups. Teachers of all grade levels and content areas can benefit greatly from learning the latest innovations in group process.

They call their particular approach, social therapy, and it is practiced at ten social therapy centers in the US. The non-profit East Side Institute runs on grants and donations and more info is available at the link below.