An injection that blocks the activity of a protein involved in aging reverses naturally occurring cartilage loss in the knee joints of old mice, a Stanford Medicine-led study has found.

The treatment also prevented the development of arthritis after knee injuries such as ACL tears often experienced by athletes or recreational exercisers. An oral version of the treatment is already in clinical trials with the goal of treating age-related muscle weakness.

Samples of human tissue from knee replacement surgeries in the joint also responded to the treatment by making new, functional cartilage, a result which suggests that in the future, knee and hip replacement may be totally unnecessary.

The treatment directly targets the cause of osteoarthritis, a degenerative joint disease that affects one of every five adults in the United States and is estimated to cost about $65 billion in direct health care costs each year. Prevention or a replacement is the only strategy society-wide, as no drug can slow down or reverse the disease.

The protein blocked by the injection, 15-PGDH, is a master regulator of aging, and is in fact termed a “gerozyme” due to its increase in prevalence as the body ages. Gerozymes also drive the loss of tissue function. They are a major force behind age-related loss of muscle strength in mice.

Blocking the function of 15-PGDH with a small molecule results in an increase in old animals’ muscle mass and endurance. Conversely, expressing 15-PGDH in young mice causes their muscles to shrink and weaken.

In bone, nerve, and blood cells, regeneration is due to increases in the proliferation and specialization of tissue-specific stem cells. However, cartilage-generating chondrocytes change their patterns of gene expression to assume a more youthful state without the involvement of stem cells.

“This is a new way of regenerating adult tissue, and it has significant clinical promise for treating arthritis due to aging or injury,” said Helen Blau, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology. “We were looking for stem cells, but they are clearly not involved. It’s very exciting.”

“Millions of people suffer from joint pain and swelling as they age,” said Blau’s colleague and co-senior author, Nidhi Bhutani, a PhD and associate professor of orthopedic surgery. “It is a huge unmet medical need. Until now, there has been no drug that directly treats the cause of cartilage loss. But this gerozyme inhibitor causes a dramatic regeneration of cartilage beyond that reported in response to any other drug or intervention.”

There are three main types of cartilage in the human body. One, hyaline cartilage, is smooth and glossy, providing a low-friction surface for lubrication and flexibility in joints like the ankles, hips, shoulders and parts of the knee. Hyaline cartilage—also known as articular cartilage—is the cartilage most commonly affected by osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis occurs when a joint is stressed by aging, injury, or obesity. The chondrocytes begin to release pro-inflammatory molecules and to break down collagen, which is the primary structural protein of cartilage. When collagen is lost, the cartilage thins and softens; the accompanying inflammation causes the joint swelling and pain that are hallmarks of the disease. Under normal circumstances, articular cartilage rarely regenerates. Although some populations of putative stem or progenitor cells capable of generating cartilage have been identified in bone, attempts to identify similar populations of cells in the articular cartilage have been unsuccessful.

Previous research from Blau’s lab has shown that a molecule called prostaglandin E2 is essential to muscle stem cell function. 15-PGDH degrades prostaglandin E2. Inhibiting 15-PGDH activity, or increasing levels of prostaglandin E2, supports the regeneration of damaged muscle, nerve, bone, colon, liver, and blood cells in young mice.

Blau, Bhutani and their colleagues wondered if 15-PGDH might also play a role in aging cartilage and joints. They wanted to find out if a similar pathway contributes to cartilage loss from aging or in response to injury. When they compared the amount of 15-PGDH in the knee cartilage in young versus old mice, they saw that, as in other tissues, levels of the gerozyme increased about two-fold with age.

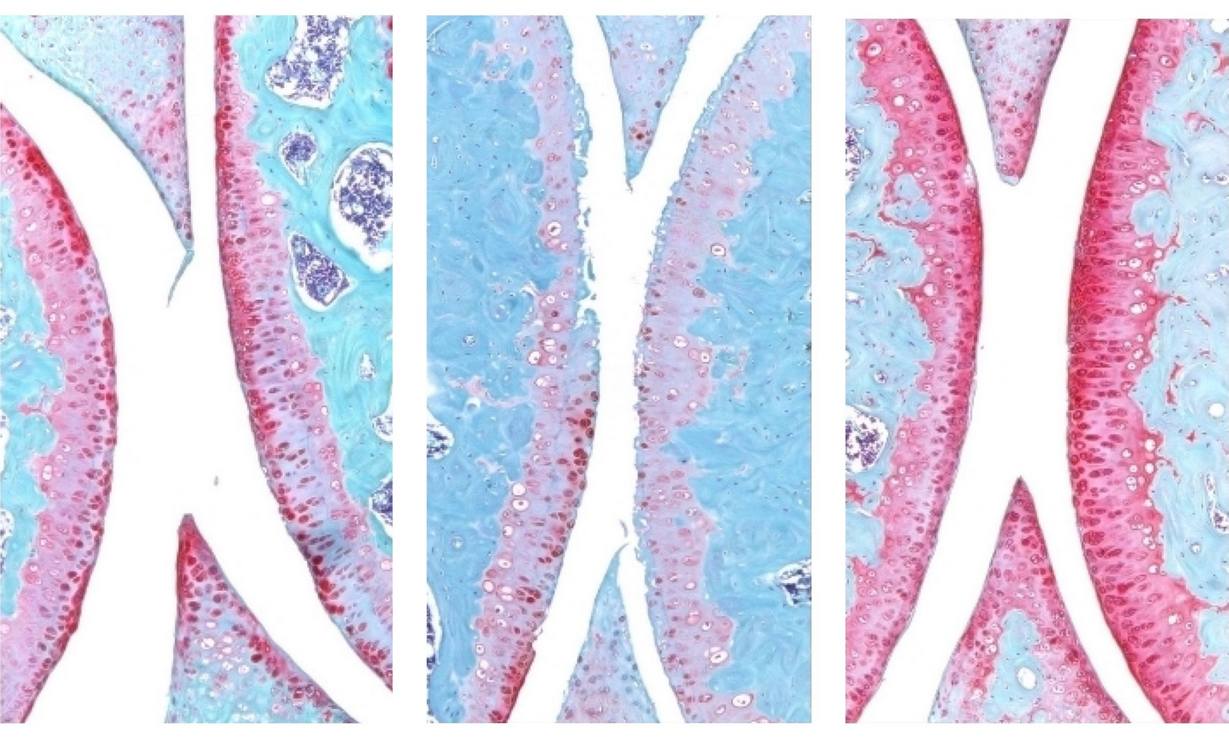

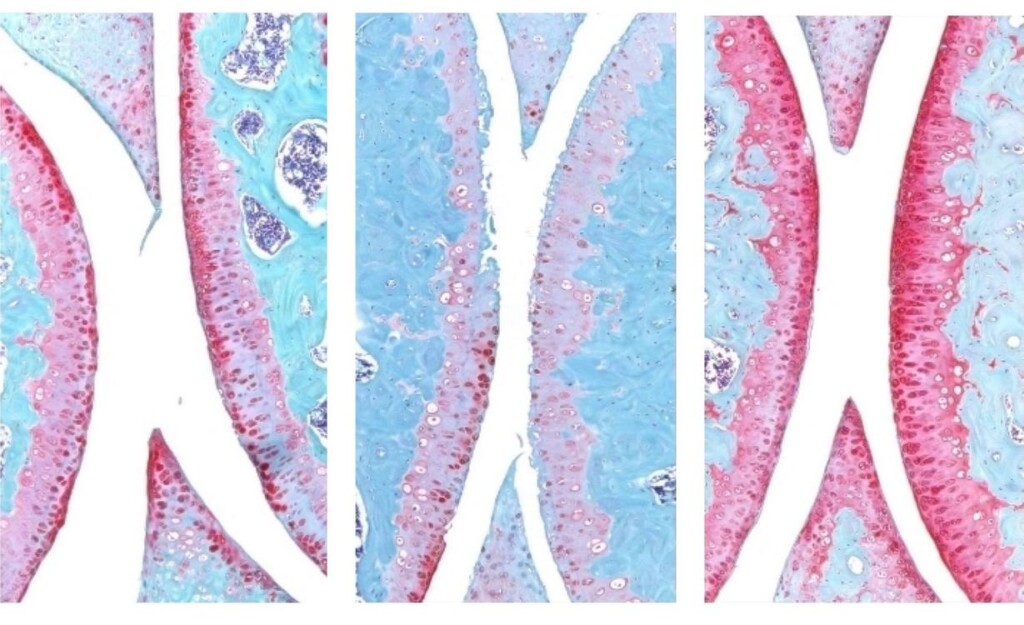

They next experimented with injecting old animals with a small molecule drug that inhibits 15-PGDH activity — first into the abdomen, which affects the entire body, then directly into the joint. In each case, the knee cartilage, which was markedly thinner and less functional in older animals as compared with younger mice, thickened across the joint surface. Further experiments confirmed that the chondrocytes in the joint were generating hyaline, or articular, cartilage, rather than less-functional fibrocartilage.

“Cartilage regeneration to such an extent in aged mice took us by surprise,” Bhutani said. “The effect was remarkable.”

Similar results were observed in animals with knee injuries like the ACL tears that frequently occur in people participating in sports such as soccer, basketball, and skiing that require sudden pivoting, stopping or jumping. While the tears can be surgically repaired, about 50% of people develop osteoarthritis in the injured joint within about 15 years.

COMBATTING AGING: Chemical Shield Stops DNA Damage from Triggering Disease–’A Paradigm Shift’

The researchers found that a series of injections twice a week for four weeks of the gerozyme inhibitor after injury dramatically reduced the chance that osteoarthritis develops in the mice. The animals treated with the gerozyme inhibitor also moved more typically and put more weight on the paw of the affected leg than did untreated animals.

“Interestingly, prostaglandin E2 has been implicated in inflammation and pain,” Blau said. “But this research shows that, at normal biological levels, small increases in prostaglandin E2 can promote regeneration.”

ALSO CHECK OUT: Scientists Find a Switch That Could Stop Osteoporosis, Making Bones Stronger in Old Age

A closer investigation of the chondrocytes in the joints of old mice and young mice showed that old chondrocytes expressed more detrimental genes involved in inflammation and the conversion of hyaline cartilage to unwanted bone, and fewer genes involved in cartilage development.

The researchers studied human cartilage tissue removed from patients with osteoarthritis undergoing total knee replacements. Tissue treated with the 15-PGDH inhibitor for one week exhibited lower levels of 15-PGDH-expressing chondrocytes and lowered cartilage degradation and fibrocartilage genes than control tissue and began to regenerate articular cartilage.

MORE STORIES LIKE THIS: 2 Years of Exercise Reversed 20 Years of Aging in the Heart, Says Longest-Ever Randomized Trial on Exercise

“The mechanism is quite striking and really shifted our perspective about how tissue regeneration can occur,” Bhutani said. “It’s clear that a large pool of already existing cells in cartilage are changing their gene expression patterns. And by targeting these cells for regeneration, we may have an opportunity to have a bigger overall impact clinically.”

“Phase 1 clinical trials of a 15-PGDH inhibitor for muscle weakness have shown that it is safe and active in healthy volunteers,” said Blau. “Our hope is that a similar trial will be launched soon to test its effect in cartilage regeneration. We are very excited about this potential breakthrough. Imagine regrowing existing cartilage and avoiding joint replacement.”

SHARE These Amazing Results With Your Friends Whose Knees Are Bad…