In a story that proves you don’t have to be a star to find a star, astronomers are excited to train the next generation of telescopes at an Earth-like exoplanet discovered by a citizen scientist.

Alexander Venner, currently studying studying at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, picked his way by hand through the data collected by a now-retired NASA space-based telescope called Kepler, which was used to examine the sky for exoplanets during a survey of 500,000 stars that ended 8 years ago.

Datasets like these are huge, and often combed through with search algorithms, but the PhD student managed what others did not by rolling up his sleeves, so to speak.

“It was completely missed,” Mr. Venner told Science Magazine about his discovery, presented at the Rocky Worlds conference in Groningen. “The best way to detect it was to actually just look.”

The reason it was missed was because the exoplanet orbits a K-dwarf star designated HD 137010. At just 146 light years away, it’s close enough for Kepler to have recorded the presence of such a small planet, and for the most powerful telescopes of the day to record it in great detail.

Scientists look for exoplanets by centering a telescope on a distant star and waiting to see a dip in the star’s light, indicating there’s something orbiting the star large enough to reduce the light signal—a planet. This is called the transit method.

The first man to ever identify an exoplanet this way concluded shortly after there must be millions of them. Indeed, the number of known planets beyond our solar system has passed 6,000, yet those which are Earth-like in orbit and mass number merely a few dozen.

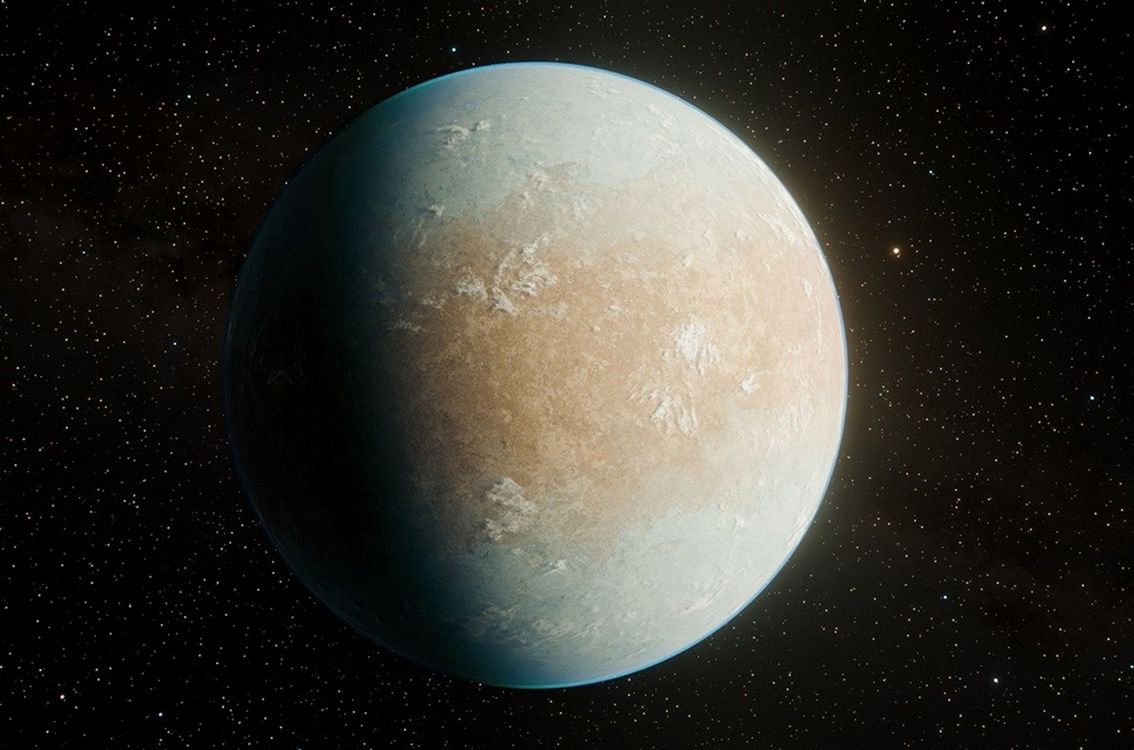

Most exoplanets are large and hot, making for easy detection because of the larger dips in light described earlier. Smaller, Earth-sized, rocky worlds orbiting within their star’s habitable zone are not only of the greatest interest to scientists, they’re also much harder to spot, since they’re cooler and smaller.

This is exactly why Venner was able to discover this planet, called HD 137010b. Search algorithms passed over its faint signal in the Kepler data. Venner came across the data through the Planet Hunters project which recruits citizen scientists and volunteer enthusiasts to search through data from Kepler and other planet-hunting telescopes to look for signals left behind by larger surveys.

Venner was thusly recruited during his time at the Planck Institute. Stumbling upon the signal dip from HD 137010, he and his colleagues determined that a planet—rather than a binary star—best explained the dip, and that by looking at the time between dips and the faintness of the signal, an Earth-sized world with about the same orbit as our planet fit the data.

STUDENTS LOOKING WHERE OTHERS HAVEN’T: The First Amateur Astronomer to Ever Discover a New Moon – And it’s Orbiting Jupiter

Venner and his teams’ findings were presented in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, and they propose that HD 137010b sits on the freezing edge of the habitable zone, attributable to HD 137010’s temperature of about 1,800°F lower than our Sun.

It’s doubly exciting because of the few dozen Earth-sized worlds known to science that orbit in what should theoretically be habitable zones—the not-too-hot/not-too-cold space where temperatures could support liquid water—many orbit M-type stars, which have a nasty habit of obliterating planetary atmospheres by spewing out high energy radiation.

MORE HABITABLE ZONE WORLDS: New Temperate Planet That Could Support Human Life Discovered in Pisces Constellation by UK Scientists

HD 137010b now presents as a really appealing target for two upcoming telescope missions: European Space Agency’s orbital PLATO telescope, a successor to Kepler due to launch in about 1 year, and the Isaac Newton Telescope on the Spanish island of Las Palmas, which is slated to begin the Terra Hunting Experiment in February.

“Many of these instruments are essentially proposing to observe particular stars, bright Sun-like stars, for many years,” in the hopes of randomly chancing upon a potentially habitable planet, Venner says. “The advantage of this star is that we already know there’s a planet with Earth-like properties.”

SHARE This Enterprising Young Student’s Huge Discovery Out In The Cosmos…