A new method for measuring blood glucose levels, developed at MIT, could save diabetes patients from having to prick their fingers several times a day.

The MIT team used a technique that reveals the chemical composition of tissue by shining near-infrared light on them—and developed a shoebox-sized device that can measure blood glucose levels without any needles.

The researchers found that the measurements from their device were similar to those obtained by commercial continuous glucose monitoring sensors that require a wire to be implanted under the skin. While the device presented in this study is too large to be used as a wearable sensor, the researchers have since developed a wearable version that they are now testing in a small clinical study.

“For a long time, the finger stick has been the standard method for measuring blood sugar, but nobody wants to prick their finger every day, multiple times a day,” says Jeon Woong Kang, an MIT research scientist and the senior author of the study.

“Naturally, many diabetic patients are under-testing their blood glucose levels, which can cause serious complications. If we can make a noninvasive glucose monitor with high accuracy, then almost everyone with diabetes will benefit from this new technology.”

MIT postdoc Arianna Bresci is the lead author of the new study published this month in the journal Analytical Chemistry.

Some patients use wearable monitors, which have a sensor inserted just under the skin to provide glucose measurements from the interstitial fluid—but they can cause skin irritation and they need to be replaced every 10 to 15 days.

BIG DIABETES NEWS: In World First, Stem Cells Reverse Woman’s Type-1 Diabetes

The MIT team bases their noninvasive sensors based on Raman spectroscopy, a type that reveals the chemical composition of tissue or cells by analyzing how near-infrared light is scattered, or deflected, as it encounters different kinds of molecules.

A recent breakthrough allowed them to directly measure glucose Raman signals from the skin. Normally, this glucose signal is too small to pick out from all of the other signals generated by molecules in tissue. The MIT team found a way to filter out much of the unwanted signal by shining near-infrared light onto the skin at a different angle from which they collected the resulting Raman signal.

Typically, a Raman spectrum may contain about 1,000 bands. However, the MIT team found that they could determine blood glucose levels by measuring just three bands—one from the glucose plus two background measurements. This approach allowed the researchers to reduce the amount and cost of equipment needed, allowing them to perform the measurement with a cost-effective device about the size of a shoebox.

“With this new approach, we can change the components commonly used in Raman-based devices, and save space, time, and cost,” Bresci told MIT News.

Toward a watch-sized sensor

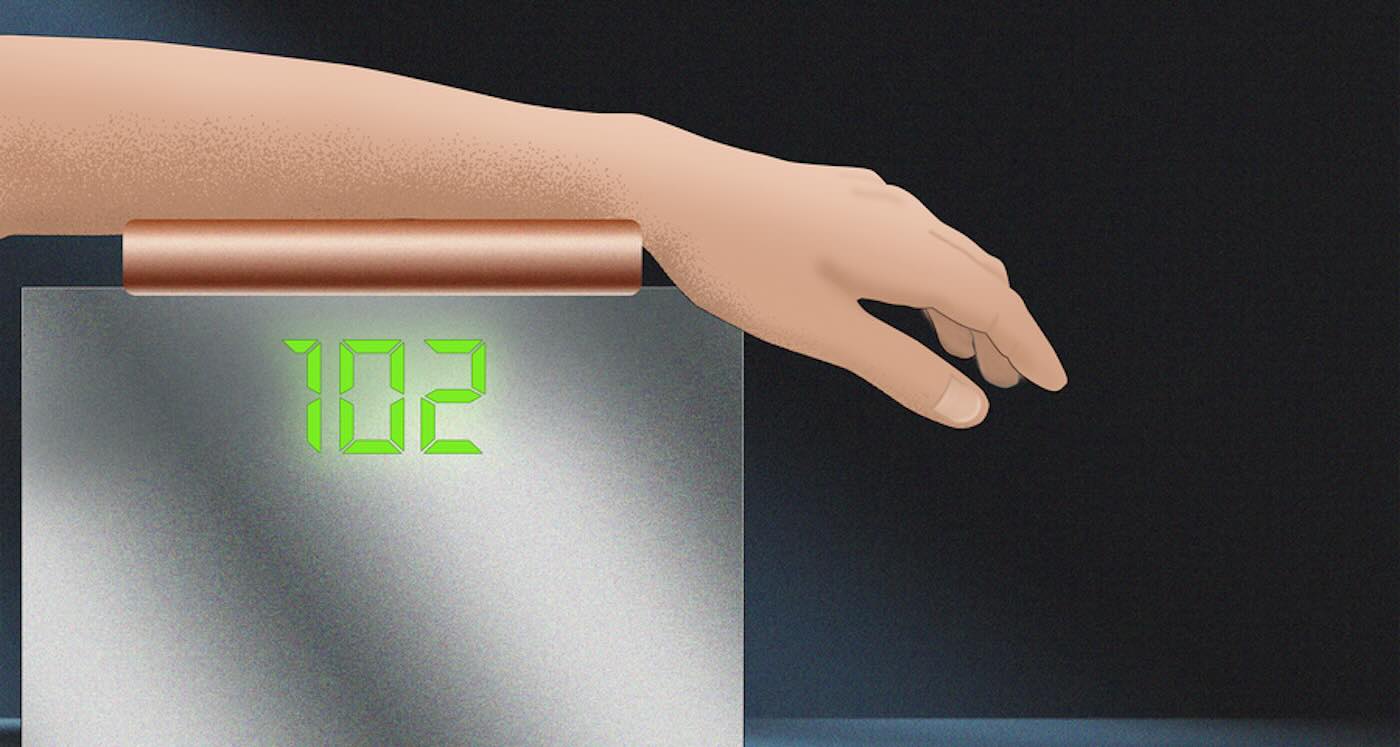

In a clinical study performed at the MIT Center for Clinical Translation Research (CCTR), the researchers used the new device to take readings from a healthy volunteer over a four-hour period, as the subject rested their arm on top of the device.

MORE GOOD NEWS FOR DIABETICS:

• Carrots May Be Key to Unlocking Microbiome’s Diabetes Defense System

• Diabetes-Reversing Drug Boosts Insulin-Producing Cells by 700%

• Type 2 Diabetes Patients Who Stick to Low-Carb Diet May Be Able to Stop Taking Medication: Study

Each measurement takes a little more than 30 seconds, and the researchers took a new reading every five minutes.

During the study, the subject consumed two 75-gram glucose drinks, allowing the researchers to monitor significant changes in blood glucose concentration. They found that the Raman-based device showed accuracy levels similar to those of two commercially available, invasive glucose monitors worn by the subject.

Since finishing that study, the researchers have developed a smaller prototype, about the size of a cellphone, that they’re currently testing at the MIT CCTR as a wearable monitor in healthy and pre-diabetic volunteers.

The researchers are also working on making the device even smaller, about the size of a watch, and next year they plan to run a larger study working with a local hospital, which will include people with diabetes.

Edited from article by Anne Trafton | MIT News

SHARE WITH DIABETIC FRIENDS On Social Media…