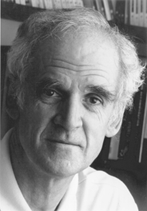

Professor Charles Taylor, a Canadian philosopher who for nearly half a century has argued that problems such as violence and bigotry can only be solved by considering both their secular and spiritual dimensions, has won the 2007 Templeton Prize.

Taylor, 75, argues that wholly depending on secularized viewpoints, without taking into account the spiritual, only leads to fragmented, faulty results. He describes such an approach as crippling, preventing crucial insights that might help a global community increasingly exposed to clashes of culture, morality, nationalities, and religions…

Need a dissertation consultant? Creative Adventures Consulting Never Shortchanges the Student

The Templeton Prize, valued at 800,000 pounds sterling, more than $1.5 million, was announced yesterday at a news conference at the Church Center for the United Nations in New York by the John Templeton Foundation, which has awarded the prize since 1973. The Templeton Prize is the world’s largest annual monetary award given to an individual.

Key to Taylor’s investigations of the secular and the spiritual is a determination to show that one without the other only leads to peril, a point he outlined in his news conference remarks. “The divorce of natural science and religion has been damaging to both,” he said, “but it is equally true that the culture of the humanities and social sciences has often been surprisingly blind and deaf to the spiritual.”

“We urgently need new insight into the human propensity for violence,” including, he added, “a full account of the human striving for meaning and spiritual direction, of which  the appeals to violence are a perversion. But we don’t even begin to see where we have to look as long as we accept the complacent myth that people like us – enlightened secularists or believers – are not part of the problem. We will pay a high price if we allow this kind of muddled thinking to prevail.”

the appeals to violence are a perversion. But we don’t even begin to see where we have to look as long as we accept the complacent myth that people like us – enlightened secularists or believers – are not part of the problem. We will pay a high price if we allow this kind of muddled thinking to prevail.”

Taylor has long objected to what many social scientists take for granted, namely that the rational movement that began in the Enlightenment renders such notions as morality and spirituality as simply quaint anachronisms in the age of reason. That narrow, reductive sociological approach, he says, wrongly denies the full account of how and why humans strive for meaning which, in turn, makes it impossible to solve the world’s most intractable problems ranging from mob violence to racism to war.

“The deafness of many philosophers, social scientists and historians to the spiritual dimensions can be remarkable,” Taylor said in remarks prepared for the news conference. “This is the more damaging in that it affects the culture of the media and of educated public opinion in general.”

Conversely, Taylor has also chastised those who use moral certitude or religious beliefs in the name of battling injustice because they believe “our cause is good, so we can inflict righteous violence,” as he once wrote. “Because we see ourselves as imperfect, below what God wants, we sacrifice the bad in us, or sacrifice the things we treasure. Or we see destruction as divine…identify with it, and so renounce what is destroyed, purifying while bringing meaning to the destruction.”

Taylor, an author of more than a dozen books and scores of published essays and who has lectured extensively, is currently professor of law and philosophy at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and professor emeritus in the philosophy department at McGill University in Montréal , the city of his birth. A Rhodes Scholar, he holds a bachelor of arts from McGill and Balliol College at Oxford University, as well as a masters and Ph.D. (D.Phil.) from Oxford. He is the first Canadian to win the Templeton Prize.

“Throughout his career, Charles Taylor has staked an often lonely position that insists on the inclusion of spiritual dimensions in discussions of public policy, history, linguistics, literature, and every other facet of humanities and the social sciences,” says John M. Templeton, Jr., M.D., the Foundation’s President. “Through careful analysis, impeccable scholarship, and powerful, passionate language, he has given us bold new insights that provide a fresh understanding of the many problems of the world and, potentially, how we might together resolve them.”

The Prize is a cornerstone of the Foundation’s international efforts to serve as a philanthropic catalyst for discovery in areas engaging life’s biggest questions, ranging from explorations into the laws of nature and the universe to questions on love, gratitude, forgiveness, and creativity. Created by global investor and philanthropist Sir John Templeton, the monetary value of the Prize is set always to exceed the Nobel Prizes to underscore Templeton’s belief that benefits from advances in spiritual discoveries can be quantifiably more vast than those from other worthy human endeavors.

The 2007 Templeton Prize for Progress Toward Research or Discoveries About Spiritual Realities will be officially awarded to Taylor by HRH Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, at a private ceremony at Buckingham Palace on Wednesday, May 2nd.

In his nomination of Taylor for the Prize, the Rev. David A. Martin, Ph.D., emeritus professor of sociology at the London School of Economics, and author of A General Theory of Secularization, a seminal work in the field, said, “His oeuvre is massive and covers issues quite central to contemporary concerns, above all perhaps the nature of self-hood and the religious and secular options open to us in what is sometimes described as secular or even secularist society. He has traced the historical evolution of the religious and secular dimensions of the world as they relate to each other with unequalled authority.”

Taylor was born in 1931 in Montréal in French-speaking Quebec, the only Canadian province where English is not the majority language. Growing up in a Catholic home where both French (his mother’s native tongue) and English (his father’s) were spoken, in a province where language is a political touchstone, spurred an early interest in matters of identity, society and the potential value of thought that runs against the common grain. Though his first degree was in history, a Rhodes Scholarship in 1952 led him to study philosophy at Oxford, where he encountered what Taylor describes as “an unstructured hostility” to, among other things, religious belief. In reaction, he began to question the so-called “objective” approaches of psychology, social science, linguistics, history, and other human sciences.

This led Taylor to his doctoral dissertation, which offered a devastating critique of psychological behaviorism, which holds that all human activity can be explained as mere movement, without considering thought or subjective meaning. Published in 1964 as The Explanation of Behaviour, it put the philosophical world on notice that a new voice had arrived.

From there he went on to write at length on Hegel, the philosopher who pioneered deep contemplation on notions of modernity – territory that Taylor was now intent on exploring anew – including Hegel, published in 1975, and Hegel and Modern Society, 1979.

In 1992, for example, Taylor wrote an article published in the book, Multiculturalism and “The Politics of Recognition” that detailed the effect of modernity on concepts of identity and self which, in turn, has had a profound political impact. He continued that investigation with his noted Marianist Lecture in 1997 in Dayton, Ohio, where he declared that the Catholic Church could find its place within the modern world by seeing Western modernity as one among the many civilizations in which Christianity has been preached and practiced. This would avoid both the total identification with European civilization which has blunted the Christian message, and also the opposite extreme of seeing modernity as the antithesis or enemy of Christian faith. It was published as a book entitled, A Catholic Modernity? in 1999. Noting the possibility of a “spiritual lobotomy,” he warned, “There can never be a total fusion of the faith and any particular society, and the attempt to achieve it is dangerous for the faith.”

Then, in 1998-99, Taylor delivered the renowned Gifford Lectures, entitled “Living in a Secular Age,” at the University of Edinburgh. The lectures, published in three volumes, offered a staggeringly detailed analysis of the movement away from spirituality in favor of so-called objective reasoning. Many expect the final volume, A Secular Age, scheduled for publication by Harvard University Press later this year, to be the most important literary achievement of Taylor’s lifetime and the definitive examination of secularization and the modern world.

The Premier of Quebec, Jean Charest, recently appointed Taylor to co-chair a commission on accommodation of cultural religious differences in public life. “The debate on this issue in our society has recently taken on worrying features,” Taylor says, “including a dash of xenophobia.” Hearings throughout the province are expected to begin in Fall 2007.

Taylor, who lives with his wife, Aube Billard, an art historian, in Montréal, and, currently in Evanston, Illinois, has said he will use the Templeton Prize money to advance his studies of the relationship of language and linguistic meaning to art and theology and to developing new concepts of relating human sciences with biological sciences.

The Foundation noted that Taylor’s selection as the 2007 Templeton Prize Laureate will launch a broad, online discussion of the question, “What role does spiritual thinking have in the 21st Century?” at its website, www.templeton.org

How is “spirituality” in this context different from dogmatic “religion”? How exactly can natural science and religion *not* be separated? I find the whole concept of merging them highly suspect. *Studying* science from a religious perspective, or vice versa, is obviously valuable. But how can we reach a secular middle ground? It seems highly unlikely, since much deeply felt religious belief exists regardless of – in some case in *spite* of – scientific evidence. For those who believe, this is as it should be. For those who don’t, ditto. Scientists don’t want religious people holding up their work to a “spiritual” barometer any more than the religious want science to call into question their faiths. The whole business seems counterintuitive, and to those who are both (like myself) this should be even more apparent.

Additionally, it appears that the Templeton Prize, as defined by Mr. Templeton himself, is an expression of two seriously troubling notions. The first being that “prizes” like this should be a competition for what is more important (in this case, religion vs. secular humanism). Second, and more disgusting, is that the symbol for this comparison is money – an assertion that is more crass to many who are deeply religious than it is to scientists (not to say it wouldn’t tick them off, too).

I agree with Mr. Taylor that there is an unhealthy air of intolerance and hostility toward religious and spiritual thought in the science community. I further agree that psychological behaviorism – and other reductive scientific notions – are damaging to ethics and morality in both religious and secular humanistic circles.

What I take issue with is how exactly he proposes we include “spiritual dimensions” into the realms of natural and social science. The “spiritual dimensions” to which he refers are an individual’s personal beliefs. True, those individuals should be freer to express them. But that’s a far cry from including them in peer-reviewed journals. After all, what if their peers don’t believe?

Spirituality as defined by Joseph Campbell is mystery. Einstein worshipped every day at the alter of this mystery… physics, earth science, anatomy, there is nothing more awe-inspiring, which is to say, we are in awe because we know only a sliver of it. To summarily omit our spiritual awareness from our scientific research is to never have another Einstein, I suppose.

I don’t know what you mean about “including beliefs in peer-reviewed journals”. It could be in the hypothesis, like, I think that because there is a force in the world that connects us, I believe _____ will happen when _____ is done… but the data collecting and physical observation and reporting can be universal scientific method. What’s so wrong about that? Just because someone doesn’t agree with your belief doesn”t mean you shouldn’t include it like this in your thinking.

My instinct, and I’m no scientist, is that science and spirituality — NOT RELIGION, though — are INEXORABLY linked. I’m FOR someone with clout and MONEY, like Mr. Templeton doing something to FREE UP the shackles we have placed over science and open our minds at least to the “neutral” position of allowing such thoughts as Einsteins to emerge and be part of the scientific DISCUSSION — as it is now, no one is even allowed to suggest anything or connection in the spirit realm.

There are definitely spiritual paths that aren’t dogmatic – probably the best known is Buddhism, which is usually considered a “philosophy” because of this unfortunate tendency to equate religion with dogma. But one can be religious without needing to shove it in other people’s faces. (I personally consider it a requirement, but I’m in a tiny minority there!) And one can acknowledge an inner spiritual reality without even identifying with any established religion.

Taylor’s not talking about muddling science and spirituality – that’s disastrous. Religion that tries to dress up as science (e.g. “creation science”) discredits both. I think that what Taylor’s getting at is acknowledging that spirituality is something essentially human, that you can’t just pretend it’s not there, and that, fully accepted as a part of our lives, it can INFORM science rather than trying to squelch it.

I’m going to overstep that a smidge further – not being an academician with a reputation to preserve, I can do that 😉 – and guess that if spirituality were cosidered a normal part of the human experience and respected as such, dogmatic evangelical religion would have a harder time finding a toehold. If wonder and awe were respected as inspired, rather than sneered at as childish and simple-minded, that hunger of the soul wouldn’t rise to such a level of desperation that cult daddies and Waco whackos could take advantage.

For Templeton to compare his award to the Nobel prize in strictly financial terms because he believes that spirituality is MORE important than “other human endeavors” is gross. He has every right to do it, but I have every right to judge it as pretentiously serving a religious doctrine to which he subscribes.

I’m not totally defending the Nobel committee – they have their problems as well. It’s the symbolic gesture that troubles and angers me.

Just as “creation scientists” are dogmatic religious zealouts dressed up as “scientists”, “spirituallity” is a neat cloak that religious leaders like to hide behind because it appears secular, but really is not.

Not that there isn’t place for personal opinion in science. To conclude certain things (“the spectacular nature of the universe leads me to believe that a God exists,” etc.) is perfectly fine. But look at the example you describe “I think that because there is a force in the world that connects us, I believe _____ will happen when _____ is done.”

This is NOT a statement that can – or should – withstand the scientific process. It is NOT an HYPOTHESIS. It is an OPINION! You *think* there is a force in the world that connects us? Where’s your evidence?! And then to use your belief to back up a logical argument? That’s patently outrageous.

I agree that to completely sever spirituality – even religion- and science leads to wacko religious zealots on the one hand, and nihilistic cynics on the other. Even worse, neither side talks to the other. How can we solve this conundrum? I honestly don’t know. But throwing money around certainly isn’t the answer.

The true beauty of science is that it provides common ground for people of any – or no – faith. It is NOT an “atheists only” club, but neither is it a system designed to provide support for people’s beliefs. It is a method by which we study the universe – plain and simple. Philosophical conclusions about scientific discoveries should be left to philosophers and poets, and, I suppose, some form of “spiritual” study. But can we do away with religion, already?

Daniel,

Perhaps your passion has clouded your understanding, or I wrote my comment without clarity, but your restatement of what I said was totally off the mark. Of course this is a hypothesis: (“I think that because there is a force in the world that connects us, I believe _____ will happen when _____ is done.” ) ‘The world is round’, was someone’s opininion, just as ‘the world is flat’ was opinion.

And, of course “I believe _____ will happen when _____ is done,” CAN certainly tested!

Just because I have stated that the connection between things is WHAT causes it, doesn’t mean the cause and effect can’t be proven to exist. Regardless of the mechanism, the cause can be proven to have an effect.

It sounds like ranting to me when you write, “You *think* there is a force in the world that connects us? Where’s your evidence?! And then to use your belief to back up a logical argument? That’s patently outrageous.”

I never said I would use belief to back up the arguement. That is where I think your passion clouds your judgement. I clearly said I would use true scientific method for all testing.

I would only use belief to think, not to show as proof.

As to “where is my evidence” of such a connection, I have personal experience. That is all the evidence I need. Many other people have the same experience.

I found this in Wikipedia when I was searching for a photo of Einstein for my On This Day in History article for March 14 (his birthday):

Albert Einstein argued that conflicts between science and religion “have all sprung from fatal errors.” However “even though the realms of religion and science in themselves are clearly marked off from each other” there are “strong reciprocal relationships and dependencies”… “science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind …a legitimate conflict between science and religion cannot exist.” However he makes it clear that he does not believe in a personal God, and suggests that “neither the rule of human nor Divine Will exists as an independent cause of natural events. To be sure, the doctrine of a personal God interfering with natural events could never be refuted…by science, for [it] can always take refuge in those domains in which scientific knowledge has not yet been able to set foot.” (Einstein 1940:605-607)

Einstein told Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals Himself in the lawful harmony of the world, not in a God Who concerns Himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.”(Brian 1996:127)