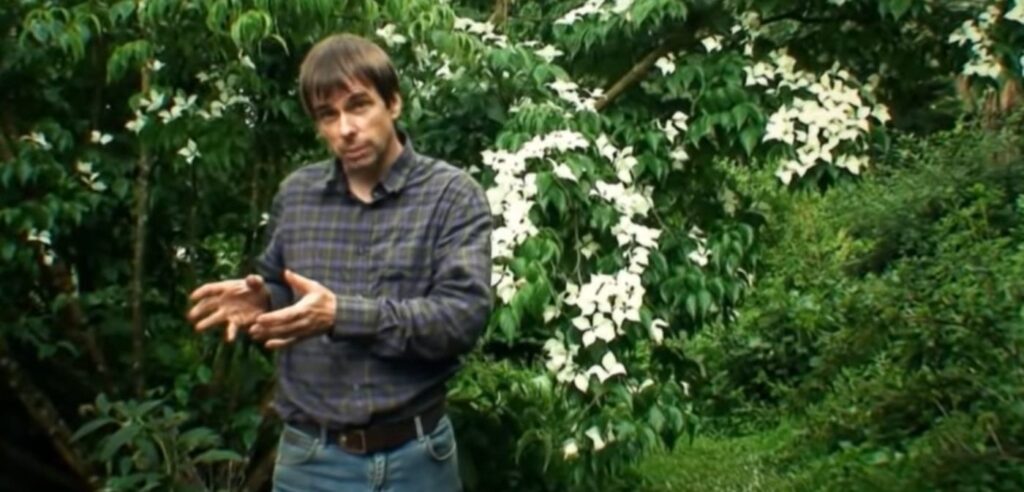

Far from pursuing the American vision of “amber waves of grain,” this farmer in England’s southwest has, for 20 years, been growing 500 different types of food in what appears to be a temperate forest.

Known as “agroforestry,” Martin Crawford’s garden is wild but tamed—a forest capable of producing tons of food with as little as a few hours’ work a month.

“What we think of as normal in terms of food production is actually not normal at all,” explains Crawford in a National Geographic short about his marvelously-tangled forest garden.

“Annual plants are very rare in nature, and yet most of our agricultural fields are full of annual plants. What’s normal is a forested or semi-forested system.”

The word ‘system’ here is important, because whereas normal farmers look to isolate certain parts of natural systems for complete control (a tactic which has become unfathomably successful thus far) Crawford’s garden’s success depends on it holding it’s own as a fully functional and complex ecosystem.

Returning to normal

Crawford explains in the video, and in his book Creating a Forest Garden, that one needs seven layers: tall trees, small trees, shrubs, perennials, ground cover, root crops, and climbers.

These could be food producing crops, but also what he calls system plants, ones which aid in nitrogen distribution or mineral accumulating, or others which attract pollinating species that eat pests.

RELATED: Cheap ‘Plant Pods’ That Can Grow More Lettuce in a Room Than Half-Acre Plot May End Hunger

In addition, he grows utilitarian plants such as those meant for weaving fibers, basket making, medicinal plants, and plants meant for fine timber as well. He even has fruit bushes spliced into existence in Cold War-era Soviet laboratories.

“It can seem a bit overwhelming, there’s just so many different species,” he admits. “You shouldn’t let that stop you from beginning a project because you don’t have to know everything to begin with, just start, plant some trees, and go from there.”

Eventually though, agroforestry systems become so big, and so perennial, as to naturally eliminate most of the work one associates with farming or gardening. Since everything is there to stay, there’s no need to till and re-till the ground, add manure, fertilizer, or nitrogen.

The canopy will hold moisture in the undergrowth, meaning that eventually, you won’t really need even to water your garden.

A more sustainable system

This lack of tilling pressure eliminates one of the major land-use changes associated with human carbon emissions. “Because of course when you [till] the soil, a load of carbon goes into the air,” explains Crawford in another film on his farm.

Furthermore, it releases micronutrients and exposes vital fungi, bacteria and other microorganisms to sunlight, often killing them, reducing the biodiversity of soil particles.

But the real sustainability of an agroforestry system comes from its diversity of species.

“It’s not the gradually increasing temperatures that damage plants, it’s the increase in extreme events,” he explains in the Nat Geo film. “By having a very diverse system whatever happens to the weather, most of your crops will probably do fine—some will fail, some may do better.”

That’s very important, explains Crawford because it’s during the next 30 years that farmers will be under the constant threat of changing weather, and will have to be able to identify quickly which species of fruits and vegetables are capable of withstanding such threats.

A growing global movement

Agroforestry is planting firm roots, and growing strong in farming families across Europe and North America. Some are even attempting to bring the practice into the infamously destructive oil palm plantations in the tropics.

Earlier this year, GNN reported that 59,400 square miles of land (15.4 million hectares) is currently utilized in Europe for agroforestry, of which 15.1 million is livestock agroforestry, while in the U.S., the 2017 Census of Agriculture found over 30,000 farms utilizing agroforestry practices, in states as varied as Texas, Virginia, Oregon, Missouri, and Pennsylvania.

MORE: Put These 5 Plants In Your Bedroom Window for a Better Night’s Sleep

“In this country [the UK] in particular, you know, farmers don’t tend to know much about trees, and foresters don’t know much about farming. And agroforestry, which is kind of in the middle of the two, therefore seems quite difficult for people like farmers to access because they’re not comfortable with trees, so that’s a potential problem,” Crawford hypothesized in a film about his garden from 2010.

It’s perhaps necessary that they do. Agroforestry systems can produce varying amounts of an enormous variety of foods; their three-dimensional nature making up for the lack of powerhouse production potential of a traditional farm.

CHECK OUT: Don’t Rake Those Leaves: Good for Your Yard, and the Planet

Organic farming, however, which is often hypothesized as an effective alternative, would require an average of 500% more land to feed the UK at current yields, while undesirably producing 170% more greenhouse gases due to the need to use overseas land, create natural fertilizer, and import the difference in production loss.

READ: Man Creates Gardens For Unwanted Bees, Grows Free Food in 30 Abandoned Lots

Hopefully Martin Crawford can inspire a generation of forest farmers through his innovative work, appealing to both dedicated agriculturalists, and lazybones who only feel like working a few hours a month.

(WATCH the National Geographic short about Martin below.)

GROW Some Positivity: Share This Story With Green-Fingered Pals…

Love this!