A much cheaper fuel cell could be on its way thanks to a breakthrough cathode built by Australian researchers that uses Gortex, the same material in outdoor clothing. Up until now, fuel cells needed a cathode which contains expensive platinum particles, worth around $3,500 to $4,000. The new cost-effective solution, featured yesterday in the journal Science, uses a thin flexible polymer that conducts electricity at a cost of only several hundred dollars, while producing the same amount of current as the platinum cathode. The plastic also exhibits increased stability.

A much cheaper fuel cell could be on its way thanks to a breakthrough cathode built by Australian researchers that uses Gortex, the same material in outdoor clothing. Up until now, fuel cells needed a cathode which contains expensive platinum particles, worth around $3,500 to $4,000. The new cost-effective solution, featured yesterday in the journal Science, uses a thin flexible polymer that conducts electricity at a cost of only several hundred dollars, while producing the same amount of current as the platinum cathode. The plastic also exhibits increased stability.

The researchers from Monash University in Melbourne suggest that as Goretex had revolutionized the outdoor clothing industry, it could hold similar promise for motorists, making the next generation of hybrid cars more reliable and cheaper to build.

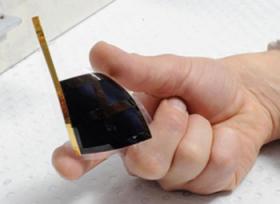

The advancement introduces air onto an electrode, where a fine layer — just 0.4 of a micron thick, or about 100 times thinner than a human hair — of highly conductive plastic is deposited on the breathable fabric. The conductive plastic acts as both the fuel cell electrode and catalyst.

Professor Doug MacFarlane from the Australian Centre for Electromaterials Science (ACES) said the discovery was probably the most important development in fuel cell technology in the last 20 years.

“The benefits for the automotive industry and for motorists are that the new design removes the need for platinum, which acts as the catalyst and is currently central to the manufacturing process,” Professor MacFarlane said.

In addition to being prohibitively expensive — the precious metal costs about $1,700 to $2,000 per ounce — the current annual world production of platinum is only sufficient for about 3 million vehicles.

The new design fuel cell has been tested for periods of up to 1500 hours continuously using hydrogen as the fuel source.

Professor Maria Forsyth, Director of ACES at Monash said testing has shown no sign of material degradation or deterioration in performance. The tests also confirmed that the electrodes are not poisoned by carbon monoxide the way platinum is.

“The small amounts of carbon monoxide that are always present in exhausts from petrol engines are a real problem for fuel cells because the platinum catalyst is slowly poisoned, eventually destroying the cell,” Professor Forsyth said.

“The important point to stress is that the team has come up with an alternative fuel cell design that is more economical, more easily sourced, outlasts platinum cells and is just as effective.”