A fascinating new discovery offers “tantalizing” evidence for the origin of multicellular development in life on Earth.

It seems related to something that had perhaps never happened before, and certainly has never happened since: a near-total collapse of the Earth’s magnetic field.

650 million years ago, there was little going on across the Earth worth writing about, but shortly after, when multicellular life did begin to emerge and diversify in a period known as the Edicarian, it started within a 26 million-year window of time when the Earth’s magnetic field plummeted to one-thirtieth its current strength.

The authors of this geologic discovery from the University of Rochester point out that this would have driven a rapid decrease in hydrogen content in the Earth’s atmosphere and rapidly increased oxidization of the air and oceans, allowing metabolically demanding activities like movement and propulsion to become more and more possible.

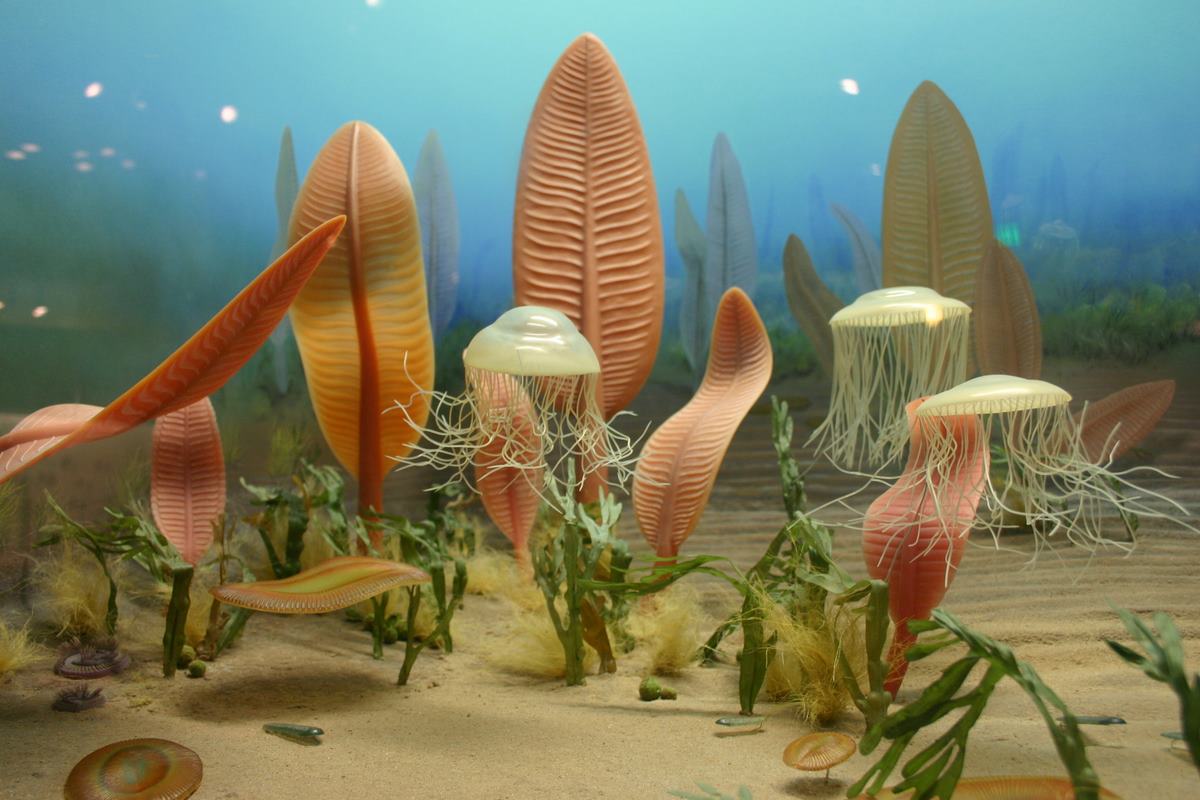

The Edicarian Period, lasting from 635 to 565 million years, currently offers the oldest confirmed fossil evidence of multicellular life on Earth. For their time they were both diverse and complex, but in comparison to any other epoch, they were extremely primitive, and consisted mostly of tubular and frond-shaped creatures but also some that had developed locomotion, including the earliest jellyfish.

Generated by the molten iron core of Earth, the magnetic field is essential for life. It does something far more important than make our compasses work or create the Aurora Borealis, it protects the planet from streams of radiation coming off the Sun called solar wind.

“Oxygen has long been identified as a key “environmental gatekeeper,” allowing for evolutionary innovation and for meeting the energy demands of animals,” the authors write.

“Although sponges and microscopic animals can survive at low levels of dissolved oxygen, macroscopic, morphologically complex, and mobile animals require a greater amount of oxygen to support their metabolic demands.”

A weakened magnetic field would allow the Sun’s radiation to strip away lighter molecules like hydrogen from the Earth’s atmosphere, and hydrogen can enter space through non-thermal processes as well. This could have resulted in an increase in oxygen sufficient enough to allow early macroscopic life to evolve in the sea.

YOU’LL ALSO LIKE: Amateur Paleontologists Discover Site of Epic Importance–400 Fossils from 470M Years Ago Amid Global Warming

Study author Professor John Tarduno and the co-authors describe the association between the earliest forms of complex life and this fall in the magnetic field, which they discovered through a particular kind of crystal called plagioclase which records magnetic signatures superbly well, as “tantalizing but unclear.”

In their study, the scientists point out that oxygen content in samples of life from the Edicarian period is significantly higher than in samples from previous periods.

MORE GEOLOGIC RESEARCH: Huge Black Diamond Sold for $4.3 Million–and No One Knows Where it Came From or How it Was Formed

The team previously discovered that the geomagnetic field recovered in strength during the subsequent Cambrian Period, when most animal groups began to appear in the fossil record, and the protective magnetic field was reestablished, allowing life to thrive.

“If the extraordinarily weak field had remained after the Ediacaran, Earth might look very different from the water-rich planet it is today: water loss might have gradually dried Earth,” Tarduno told Rochester Univ. press.

SHARE This Very Interesting Potential Watershed Moment For Life On Earth…